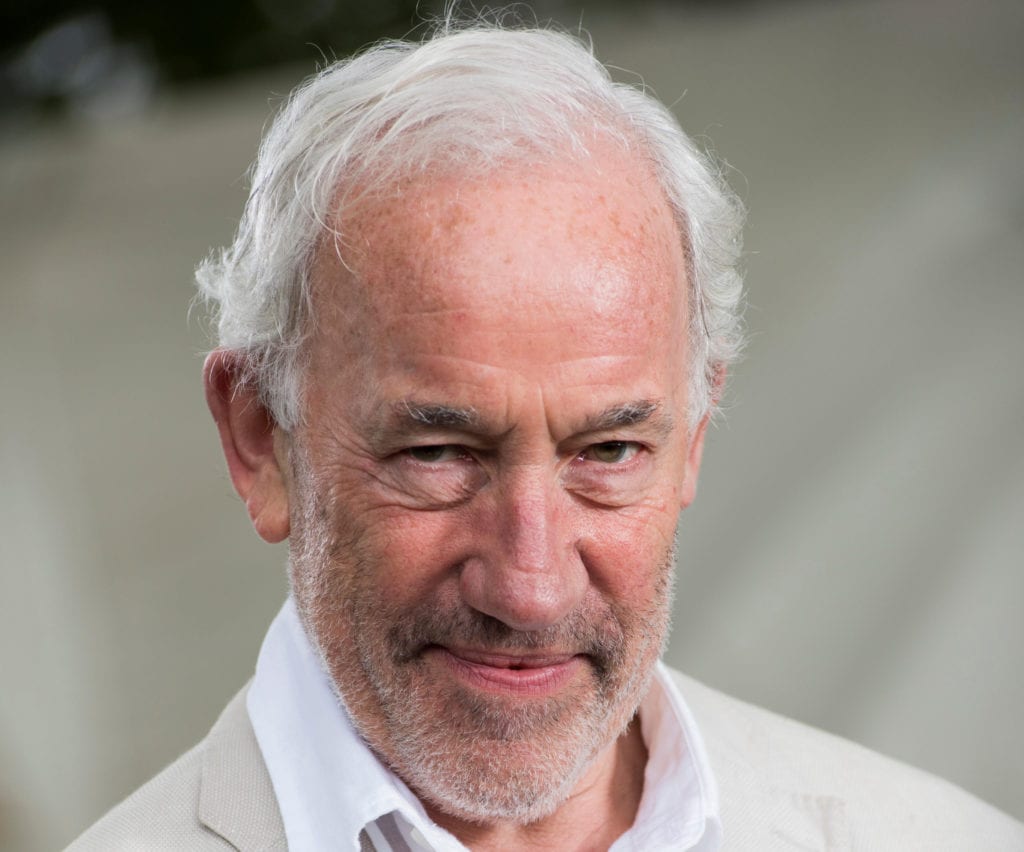

Simon Callow On His Passion For Charlie Chaplin

Slapstick Festival will be welcoming one of the country’s greatest living actors, Simon Callow, to Bristol on the 21st January to present his personal tribute to Charlie Chaplin, a man he considers to have been a major influence on his own career.

In the following excerpt from Simon’s autobiography – My Life in Pieces: An Alternative Autobiography by Simon Callow (which can be bought online here) – we get an insight into what to expect from the show, which also features screenings of three of Chaplin’s masterworks; The Vagabond (1916), Easy Street (1917) and The Pawn Shop (1917 ) and features a live musical accompaniment by The European Silent Screen Virtuosi.

For more information about the event please visit Colston Hall’s website.

“During my lifetime, Charlie Chaplin, that multifaceted genius, more famous in his day than Jesus or the Buddha, has been consistently under-rated, not least by actors who, for the most part, profess themselves scornful of the ostentatiousness of his technical skills, nauseated by his sentimentality, and unamused by his comedy. I have always been bewildered by this view. I was introduced to his work by a grandmother who was addicted to it. In those pre-NFT, pre-video, prehistoric days, we would go all over London to catch them. Sometimes the tiny Clifton cinema on Brixton Hill would be showing a three-reeler alongside a Tartan movie, and the cinema in Waterloo Station was a pretty good bet, too, though you never knew what you might get. Of the feature films, especially the ones in sound, there was very little sight. My dear old grandma, a woman who otherwise betrayed very little sense of humour, would shake with laughter, tears rolling down her cheeks, as she re-enacted the scene in The Gold Rush where Chaplin eats his boot. She had no particular mimetic gifts, but somehow she managed to suggest the incongruous delicacy with which the little tramp addresses his task. When I finally saw the film, it was remarkable how much of it she had been able to convey, which I take to be a great tribute to him: it had made such an extraordinary impact on her. His absolute mastery of his own physical instrument is phenomenal, his expressiveness unparalleled. When, as a very young man, he was appearing with Fred Karno in a theatre in Paris, playing the drunken toff which was his most famous role before he created The Tramp, he was summoned at the interval to a box where he was gravely informed by a stocky bearded man with peculiarly penetrating eyes, `Monsieur Chaplin, vous eles WI artiste.’ It was Debussy.

“Both in conception and execution, Chaplin was in a league of his own. The character of The Tramp is a creation of the highest brilliance. In his great book Chaplin: Last of the clowns, the American critic Parker Tyler identifies the elements — the hat, the walk, the moustache — showing where they came from and how Chaplin assembled them; what is harder to explain is why the strange child—man with his tottering, oscillating walk, his bowler hat and his bendy cane is at the same time so funny and so affecting, or how Chaplin makes of him a universal image of humankind, indestructibly optimistic regardless of the setbacks inflicted on him by a capricious destiny. Where is he from, who is he? He has no name, being known only as The Tramp, though he is scarcely what we think of today as a street person. He has distinct sartorial and social aspirations; he is gallant and fastidious, and is a defenceless victim of Cupid’s dart, endlessly falling unsuitably in love at first sight. But he comprehends nothing of the world. He fails to understand that his adorable moues and dazzling smiles hold no sway against the musclemen and plutocrats to whom the women for whom he falls are attached, nor has he the confidence to assert himself against bullies and figures of authority, or the skills to hold down a job. In love and in work, he is unceremoniously shown the door, ending up over and over again in the gutter. But he always picks himself up, brushing himself down with some elegance, as if he were his own valet, proceeding, generally in the company of someone equally ill-favoured, to the next rejection, the next infatuation, the next dashed dream. Hope springs eternal. It is the inevitable repetition of failure, and the constant witty assertion of dignity, that speaks so deeply to us.

“From the beginning, even before the arrival of The Tramp, Chaplin the writer and director was ceaselessly inventive, and his increasingly ambitious structures take the modern world on board with growing complexity. In City Lights, The Tramp is nearly overwhelmed by the sprawling vastness of the metropolis; in Modern Times, he is literally chewed up and spat out by the great heartless machines he is called on to operate. He scarcely belongs to the world in which he finds himself, but, like a cat or a drunk, he negotiates it with crazy grace, dancing away from danger as the structure disintegrates around him. Politically speaking, Chaplin was a radical populist in the mould of Dickens: instinctively identifying with the disadvantaged, naturally suspicious of the establishment, acutely conscious of the dehumanising effect of organised capital. In the America of the Fifties, this meant that he was a de facto Communist, though he was no such thing.

“It was inevitably difficult for Chaplin to maintain the reckless improvisatory brilliance of his early movies. His projects took longer and longer to gestate and indeed to shoot, with a resultant loss of brio; his reluctant embrace of sound robbed them of some of their expressiveness and led to his adoption of somewhat ponderous narrative procedures. There is scarcely a moment of his own performances within them, however, that is without some touch of genius: in The Great Dictator, Hynkel’s dance with the globe and the barber shaving a customer to Brahms’ Fifth Hungarian Dance, the murderous bigamist’s dazzling prestidigitation as he counts up his ill-gotten gains in Monsieur Verdoux. It is in such moments that the golden legacy of Chaplin’s Music Hall background is at its most evident. Elsewhere characterisation and even mise-en-scene tend to creak; the liberal humanitarian message of the films is spelt out rather too clearly, no doubt. The truth is that Chaplin’s art was perfectly suited to the early cinema, and he exploited it more brilliantly than anyone else had done: the medium and the man were made for each other. Then the medium changed, and nothing that he was able to do, despite all his wealth and power, could stop it in its evolution. The Music Hall, too, had died, leaving him stranded in a different world of expression, a point movingly made in Limelight, which should, by rights, have been his last film.

“No actor and no film-maker can fail to learn from the early, pre-sound films, which, especially when shown with live accompaniment as intended, achieve a kind of perfection and create a kind of exhilaration which later cinema has found hard to match.”