Best of The Best – Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd

Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin. All three began their careers more than a century ago, yet all still maintain their places as the greatest names in on screen comedy. Their films are still constantly discovered by new generations of lucky audiences who can now see them with worthy musical accompaniment – in Chaplin’s case, of his own composition.

What was special about these three was that they were not only the stars, but conceived, wrote and for all practical purposes, directed their own films. They were the total creators. Needless to say, they performed all their own stunts, however perilous: there could be no doubles for such personalities.

For Slapstick 2022 we have chosen each one’s last or penultimate silent film. Talking pictures had arrived, with The Jazz Singer (1927), but our stars did not rush to adopt sound, and Chaplin, though he was to make use of musical sound-tracks, did not speak on screen until 1940.

Keaton’s marvellous The Cameraman (1928) was the first film he made after giving up his own studio to move to MGM – a sacrifice of independence which he rightly came to regard

as the worst mistake of his life. His budget was assured, but he was an employee, subject to the producer’s final word and whim. He was no longer permitted to risk doing his own stunts – and no-one else could do them.

Perhaps the producers had not yet learned to exert their full control when he made his first MGM film The Cameraman (1928). Despite the studio, The Cameraman (1928) still has the qualities of Keaton’s great silent films: his uniquely expressive physical comedy that belies the “stone face”, in the service of a gripping narrative.

The film was Keaton’s penultimate silent movie, as was Harold Lloyd’s spectacular The Kid Brother (1927). Lloyd, like Chaplin, retained his creative autonomy and was one of the comparatively few actors to make a triumphant transition to sound films.

Lloyd, sporting his indispensable lens-less horn-rimmed spectacles, plays Harold Hickory, a hick from Hickoryville, who plays the substitute housewife in a family of overly manly men. He has a chance to prove his worth and clear his family name when a group of con artists menace town.

It is an ingenious blend of slapstick, horror, romance and inventive gags. It was one of Lloyd’s own favourites and one of most impressive monuments of silent comedy

Upon release, it was a smash hit, both at the box office and among critics. Made at the apex of Lloyd’s career – and of silent film – it is undoubtedly one of the most impressive pieces of silent comedy.

It is as common for filmmakers to have a favourite as to have a film they try to forget.

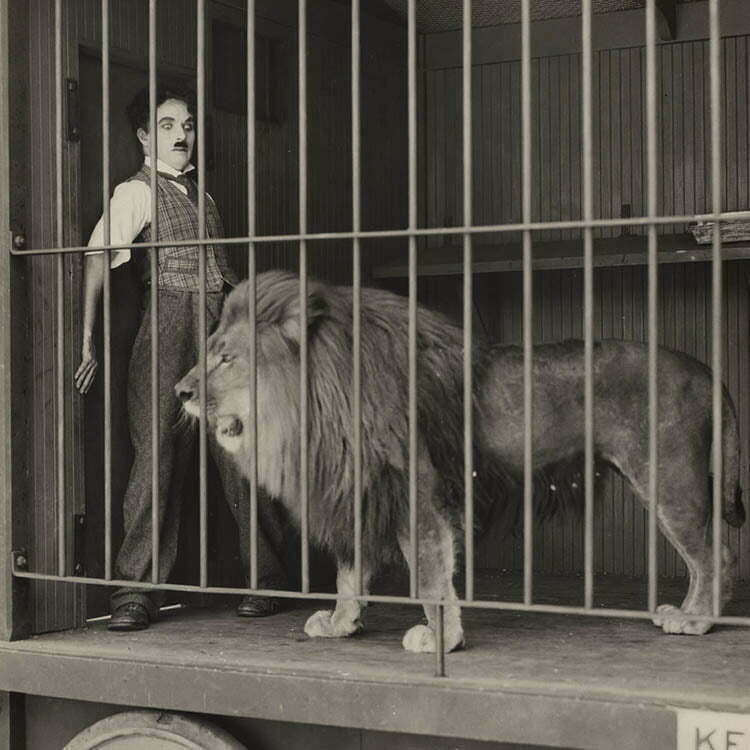

In Chapin’s case the making of The Circus (1928) proved the worst year of his working life. The trouble was not the film but the circumstances surrounding its production.

Throughout the year he was battling a merciless divorce case brought by his wife Lita Grey. Her lawyers fought – and sometimes succeeded – to take possession of Chapin’s assets, including the studio and the negatives, which the crew was always having to secrete or smuggle elsewhere. This was only the start.

The shooting began with the difficult tightrope scenes for which Chaplin and the film’s romantic lead Harry Crocker, had been tirelessly rehearsing. The scenes were successfully shot – but the lab fouled up all the negatives.

Then the set was destroyed by a fire. Because of delays, when they went back to reshoot location scenes, they found the places had been transformed by Hollywood’s rapid development.

Finally, with relief, they set up the film’s final scene in a remote location, where the whole horse-drawn circus train goes off into the distance, leaving Chaplin deserted and alone. All was ready, but when they returned in the morning, everything had disappeared, stolen by mischievous students.

Incredibly the film was finished – to become one of Chaplin’s finest and most faultless silent comedies, with scenes of incredible virtuosity like the hall of mirrors or the climactic scene where Chaplin, balancing on the high wire, is assaulted and de-trousered by a gang of monkeys. It received a special award at the very first Oscar ceremony (nothing like today’s spectacle – just a banquet in the Roosevelt Hotel). But for Chaplin it would always evoke memories of that tormented year.

Forty years later, in 1968, Chaplin finally felt able to return to the film, to release it with his own accompanying score, and a title song, ”Swing Little Girl”, for which a top pop singer of the moment, Matt Monro was contracted. However, Chaplin’s musical arranger Eric James however decided that the 81-year-old Chapin performed it better, so it is his voice we hear over the titles of The Circus.

These three great films all have one notable cast member – a monkey, who saves the day for Keaton, leads the de-bagging of Chaplin, and helps Lloyd sail. This unique simian star is Josephine, whose showcasing career in major films extended from these three films and Street Angel (1928) all the way to Arabian Nights (1942).

But Josephine is not the only thing these films have in common. They represent the finest work of the three great comedy legends of cinema, and they mark the climactic end of the silent era. They also happen to ALL be featured at the 18th edition of Slapstick Festival. Be sure to seize this opportunity.