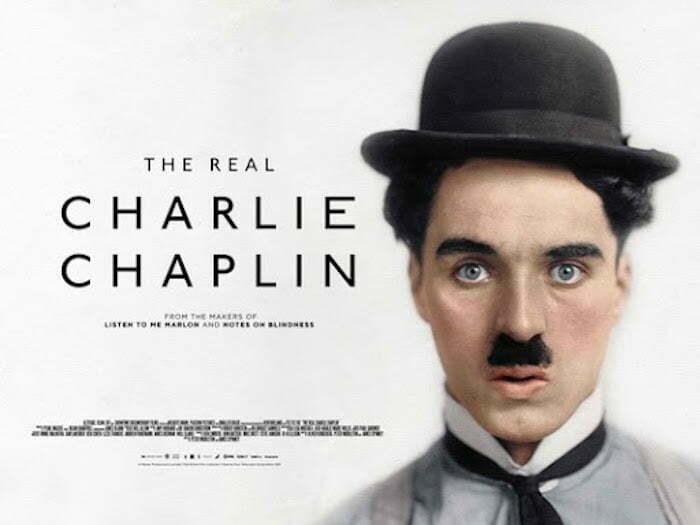

Review: The Real Charlie Chaplin

The following is a review of The Real Charlie Chaplin, originally published for Silent London and reproduced here with the kind permission of the author Pamela Hutchinson.

THE REAL CHARLIE CHAPLIN

It’s a bold, almost alarming title. At this distance, can it be possible to uncover The Real Charlie Chaplin? And if there is something hidden in the biography this most famous of filmmakers, one that can without trepidation be called an icon, might those of us who love his films really want to know?

Rest easy then, as this documentary by Peter Middleton and James Spinney (Notes on Blindness) has no disturbing revelations. That is, as long as you have already been reading those large gaps between the lines of his biography. Chaplin liked the company of young women – girls, in fact. He married teenagers. He sometimes (often?) treated them badly. It’s a been said before and it is stated again here without excuses or attacking the women such as Lita Grey who testified to his ill-treatment. This has been trumpeted in some quarters as a belated #MeToo reckoning for Chaplin. That would be very belated. In truth we have always known this, but some fans refuse to hear it.

We learn also that he was temperamental, even as a child, that he was prone to self-pity, and finally was a distant father. The last words in this documentary are given to his daughter Jane, who waited years to get to know her famous dad, and found herself finally alone with him when she had all but given up hope. Also to his final wife Oona, who wrote so much about their life together and then destroyed her own words before she died. Thus the films ends as poignantly as it had began, in Chaplin’s tough, deprived childhood, and his own cruel abandonment by his father. Such cycles are common, we understand. Chaplin was flawed. The films, mostly, are not.

Many devotees will flinch at even that, but The Real Charlie Chaplin is no hitpiece: it’s an elegant, and sympathetic introduction to the man’s work and life, narrated in soothing tones by actress Pearl Mackie. She played Bill Potts in Doctor Who, and she’s from south London, as are the two directors – which matters, just a little. The Chaplin story as they tell it is a diverting way to spend two hours. We follow his path from rags in London to riches in Hollywood to comfortable if perhaps bitter exile in Switzerland.

We see his brilliance and creativity in comedy, his sudden fame and prolonged success, as well as the grisly moment that a certain faction of the American establishment turned against him. His punishment was extreme, in proportion to his previous adulation, you might say, rather than his supposed political crime. His incriminating remarks on communism are quoted here, which are all in a direct line of thought from his cathartic early film comedy, described in this film succinctly as: “The Tramp not only stands up to the man, he gives him a kick up the arse for good measure.” Fellow traveller? Of the funniest kind.

However, it was the murky, messily unresolved case of Joan Barry, dredged up for political ends, that really did for him. The motives of his accusers were far from honourable and no one comes out of this episode with a clean slate.

Illustrating the tale, here are film clips, archive images and the occasional set of distressed mock intertitles. There are few dates and facts – it’s a story rather than a lecture – but there is a certain candour in its tone, despite the absence of shock revelations. As a primer on his career, it gives more the sense of the man and his art, rather than a full filmography. As such, it’s possibly to pick at the odd dropped stich: the voiceover states that Chaplin scored his films, before going on to describe him making The Kid. You could read that as ahistorical, or you could concede the broader point that eventually, musical composition was another string to his bow. A caption on screen refers to Minta Durfee but the voiceover calls her “someone” which tells you the knowledge level that the film is aimed at.

There is something new here, and it provides a dash of welcome cockney colour, if nothing else. A recently rediscovered interview conducted by Kevin Brownlow in the early 1980s with one Effie Wisdom, a neighbour and friend of Chaplin’s from his youth. In re-enactments, Wisdom is played by Anne Rosenfeld, and Brownlow is played by Dominic Marsh. Wisdom recalls in uncanny detail conversations from their childhood and from his return visit to London as an old man, as well as the thrill of seeing him perform on stage as a young boy, and his native accent: “Common, like me.”

If you’re looking for the real Charlie Chaplin, perhaps it’s Effie Wisdom’s young pal we need to think of, the boy who hadn’t had his elocution lessons yet.

The Real Charlie Chaplin will be screened on Saturday 29th January 2022 at the Watershed in Bristol.

The above article was originally written for Silent London (see https://silentlondon.co.uk/2021/10/14/london-film-festival-review-the-real-charlie-chaplin/) and is reproduced with permission of the author Pamela Hutchinson